Boyden’s Global Leadership Matters focuses on conversations with global leaders whose work and leadership are grounded in a commitment to having a positive impact at home and abroad. The interview series sheds light on what global leadership looks like today and tomorrow, and uncovers the importance of cultural and international awareness in leadership.

•••

Before he was the CEO of the Aga Khan Foundation Canada, Khalil Z. Shariff grew up as the son of parents who fled instability in East Africa for Canada in the 1970s. With these roots, he sees Canadians as having a unique, and critically important point of view to take on global leadership roles.

Educated at UBC and Harvard Law School, Khalil was previously a management consultant at McKinsey & Company and has served in a variety of roles with the Harvard Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. He currently sits on the boards of the Global Centre for Pluralism and the Institute for Canadian Citizenship.

Khalil talked with Boyden’s Alain Pescador about the meaning of pluralism, Canada’s unique position in global affairs and the three reasons why pluralism is important in leadership.

•••

Alain: What kind of environment did you grow up in and what aspects of your life set you up for a career that is strongly tied to international issues?

Khalil: Well, I think the most salient point about my background, and the one that I find most personally moving is that I am the child of parents who fled East Africa during a difficult moment in Uganda's history and we were welcomed by Canada.

It is a testament, of course, to their own resilience and the support of their community, but also to Canada. We were, first, the fortunate beneficiary of Canada's opportunities and its conception of what its international obligations and responsibilities required. Within a generation, my family went from being a recipient of Canada’s international outreach to helping shape those efforts. I think that's a distinctively Canadian story.

That personal experience has probably been the most important preparation for my current work. I experience it as a deeply Canadian role because we are being called upon, maybe more so at this moment than we have for many decades, to articulate, and then to enact, a certain version of Canadian global leadership. To invent it, anew, in response to a dramatically changed global environment.

Alain: You mention Canadian global leadership. What does that look like to you?

Khalil: Canada represents a set of ideals that the world is sorely in need of. Principal among them is Canada's commitment to pluralism, which we understand to mean a respect and an admiration for diversity; that people from different backgrounds and walks of life, people with different views can build a life together that is richer than if they were amongst people who were only the same.

Canada has what I consider to be the most sophisticated and elaborate version of that principle being worked out in practice. It has a long history; some would say it goes back to at least [Louis-Hippolyte] La Fontaine and [Robert] Baldwin. David Hackett Fisher’s books talks about [Samuel de] Champlain and his vision for what it meant to build a new world when he came to what is now Canada, escaping the wars of religion in Europe and seeking to transcend that kind of conflict here.

Others still, including some of our most insightful and interesting Indigenous leaders, would say this goes back to time immemorial, the idea of bringing diverse people together was a core part of an Indigenous worldview. Not to say there was no conflict. Conflict is a permanent part of human society, but there was always a way to think about inclusion and preserving and respecting difference.

So, Canada has a long history that is being played out today. I think the way this plays out is that Canada has demonstrated a level of generosity and solidarity globally. We’ve been deeply thoughtful about not only our interests and how our interests are tied up with the fate of the world, but also the ethical responsibilities that we have. Partly that's because so much of the citizenry of Canada relates to the immigration story, in some way or another. Maybe it's generations before you can find an immigrant in your family, maybe it's weeks or days.

That is something that ties this country together. People have a sense of what's going on in the world and our obligations. I do think that Canadian global leadership means being an excellent Canada at home and being ready to work with people around the world to support some of those values, principles and ideals elsewhere.

Alain: You speak about Canada being a successful and unique experiment in pluralism and I would agree with that. But does that make us more globally interconnected and a more global country? Are we prepared to play a leading global role in the world?

Khalil: It's an excellent question, and I think it's probably a journey that's never quite complete. Being global is not one thing, it's a bundle of things, and every country in the world is being forced to reckon with what being connected to the world means for that country. The area in which we are deeply global is the make-up of our population. We are on a trajectory to become an increasingly globalized citizenry and some of our cities are now the most diverse in the world.

Whether as a matter of trade, foreign policy or economic linkages, we may not be so global as others. What is undeniably true is that the world is increasingly within our borders, however our economic ties to the world are much less widespread than they could or should be.

I don't think I’m saying anything terribly insightful here, that the economic weight of the American market creates such a gravitational pull for most of Canadian enterprises that the rest of the world seems both far off, and maybe an unnecessary indulgence. But we are learning how important it is for us to have eggs in many baskets. We are entering an era of the proliferation of economic relationships around the world by Canadian enterprises in a way that has not been the case for the last half century.

With respect to extraordinary efforts of our higher education institutions, we're seeing an increasingly globalized research and education infrastructure, which is very exciting.

For my taste, I think there's still too much focus on Europe and the US but that, too, is changing. We're now seeing relationships proliferating throughout Asia and some beginning in Africa, and this is a trajectory which is now undeniable. It's going to require us to operate in different ways, but it's very possible to do, and we're well positioned as a country to be on the cutting edge of the knowledge economy and the knowledge society, by creating real bridges of knowledge among countries around the world and being a hub for that. I think that would be very exciting for Canada.

Then, of course, the pandemic has reminded us that we are, indeed, interdependent on core questions of quality of life. Our livelihoods are connected to our health. Increasingly, that realization requires a shift in attitude and ethic, compelling us to step up and contribute to the quality of life for people around the world. We now know that there's no possibility that Canada can simply create some kind of beautiful country with a high quality of life that is sheltered from the world. It was never ethically tenable and it is now clear that it is not practically tenable. Covid taught us that we are going to rise and fall as a global humanity together.

Alain: Canada plays a significant part in the work of the Aga Khan Development Network. What makes Canada a key player in the developmental agenda of the AKDN? And what role does the Aga Khan Foundation Canada play in this work?

Khalil: First, worldwide, Canada is one of the most important financial and intellectual partners in our work in Africa and Asia. In many of our most significant efforts over the last four decades, Canada has been a very important, central, and often an early partner. There is the establishment of the Aga Khan Rural Support Program in Pakistan in the early 1980s, which has become a flagship benchmark for how to work in rural environments and to really create economic and social opportunity for isolated environments. There is our work in higher education with the establishment of The Aga Khan University and the University of Central Asia. Here in Canada, there is the Global Centre for Pluralism.

Second, Canada has historically been a generous donor and a leading thinker on development issues. Remember that our current global official assistance regime starts with a report by Lester B. Pearson. The World Bank president at the time turned to Pearson to help outline how this is all going to unfold. So, the Canadian legacy around development assistance goes back to those very early days, and that generosity, that outlook, has been very important.

Now, I don't think we can rest on our laurels. All of this has to be reinvented and extended in light of new environments and new responsibilities. The ingredients are all there and the opportunity for Canada to continue to play a leadership role on development issues would be very welcome.

Alain: So how can Canada be more impactful in the world?

Khalil: Two things come to mind immediately.

The first: it's not just about the government. This idea of civil society and the citizenry is really important. We know Canadians are ready to engage and organize in all kinds of ways. We want to continue to have this stream of people taking on Canadian values. We don’t want Canada to be seen as some kind of a sequestered refuge from the world but rather a trampoline from which people continue engaging back at home and in other parts of the world. I think that will be a very important part of the cultural fabric of the citizenry.

Second: Canada must recognize that the world has become more fragile. We always have a choice, we can either flee fragility or run toward it. We have to figure out how to deepen our convictions and become savvier about how we can run toward fragility and support stabilization in many parts of the world. That could be fragile economies, security situations and climate fragility. That requires hard work and work that may have an uncertain payoff or requires very long-time horizons. But Canada is going to be an acceptable and welcome player in a lot of fragile places. Our convictions and our courage to do that is really very important.

Alain: In a post-pandemic world, what’s your vision for the impact that the Aga Khan Foundation Canada can continue to have globally?

Khalil: We really need to think hard about building and deepening strong institutions around the world. That's everything from a village council in a remote part of Afghanistan to a world class university in Nairobi, and everything in between. We've learned that people cannot survive the vagaries and volatilities of the world alone and this is not about individual heroes transcending their circumstances. People need to recognize that in this part of the world we benefit from a dense network of institutional supports that allow us to be successful despite so much volatility. We need to extend that institutional thinking around the world and we need to support, catalyze, sustain and improve strong, deeply rooted institutions.

We've learned that knowledge is a central currency of advancement. After all, the pandemic to the extent that it's been overcome, has been overcome because of an extraordinary advancement in scientific knowledge with vaccines. However, we also learned that if you owned the knowledge and the apparatus for that knowledge, you were in front of the line, and if you didn’t, you were at the back. Allowing people around the world to participate in the knowledge revolution is increasingly critical.

We must reinforce our work on pluralism. We saw how fragile our ability to really embrace diversity is during the pandemic. I often think about how BTS (the Korean pop group) went to the White House calling for respect and speaking out against the upswing in anti-Asian hate that resulted from the pandemic. It's almost unimaginable to think that the origin of the virus somehow resulted in anti-Asian sentiment, but it shows how much work we have to do to safeguard our ability to live, work and benefit from a diverse society.

Finally, our notions of global citizenship and solidarity are going to have to be reenforced. We need to raise awareness and understanding of our interdependence, and how our ethical responsibilities can be effectively discharged in a complicated and rapidly changing world where we have to believe that we’re not only in this for ourselves, but that we’re in this together.

Alain: I know those are the principles that you speak about when responding to a global crisis, so thank you for taking us through your thinking. Last question, why is pluralism important in leadership? Is there such a thing as pluralistic leadership?

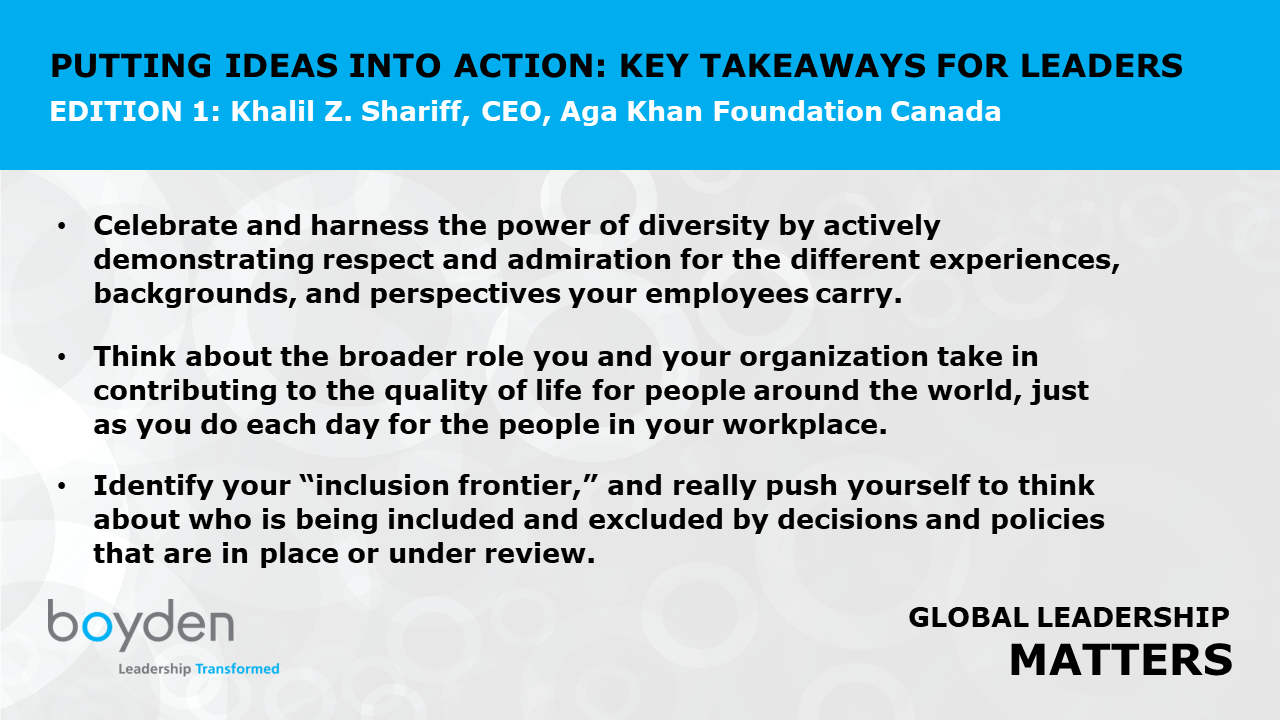

Khalil: There absolutely is such a thing and I think it’s increasingly important. I’ll give you my three reasons.

First: as an ethical matter, it’s how much marginalization has cost people and our society. It’s no longer tenable as a leader to ignore this. What’s our inclusion frontier – who are we including, and who are we excluding? Our ethical duty, especially in a diverse environment like Canada, is to be ferreting out all the dimensions of exclusion that continue to plague our organizations and institutions.

Secondly, there is a practical reason. Diversity is an asset to economic and social advancement. Google did some research on the most effective teams, called Project Aristotle. One of the things they uncovered was that teams that made the best and most interesting contributions were the most diverse. Even at the frontiers of the knowledge economy, the ability to work in diverse settings and take advantage of diversity will allow us to capture the opportunities of the knowledge economy.

The third reason why pluralistic leadership is so important is because we are again at a time in world history where the forces tearing us apart feel very strong. If we are going to overcome the human tendency toward conflict and violence, when the mechanisms for large scale violence are so available and therefore the consequences are so severe and disastrous, we’re going to have to commit ourselves, in principle and in practice, to ensuring that difference never translates to division and conflict. That instead difference means diversity and the ability to make unprecedented advances in the common good. And that, I think, is going to be the burden on all leaders.

•••

•••

•••

Khalil Z. Shariff is the CEO of Aga Khan Foundation Canada. AKFC is an international development organization and registered Canadian charity. Since 1980, the Foundation has improved millions of lives in Africa and Asia, working in partnership with the Government of Canada and diverse Canadian institutions and individuals. AKFC is an agency of the global Aga Khan Development Network, one of the largest and most respected development organizations in the world.

Alain Pescador is a key member of Boyden's Social Impact Practice, with 12+ years of international experience leading not for profit initiatives, building thought leadership platforms, and advising politicians, NGOs, and public intellectuals. Alain’s work specializes on recruitment mandates with a global angle, working with executives and boards to instate forward-thinking leaders who strive to create a lasting impact in the world. A citizen from Canada and Mexico, he brings to his work a vast network of contacts in government, business, civil society, arts & culture, and academia.